BRIC was original acronym for the four emerging market nations of Brazil, Russia India and China. By 2010, the emerging market nation of South Africa showed so much promise the initial “S” was appended to BRIC, and thus henceforth known as BRICS. At the time, quarterly GDP growth was remarkable as demonstrated in the graph below.

Guest post by Mike Scrive of Accendo Markets

USD/ZAR reached a high of 7.9567 by the end of May, 2009 and began a long steady strengthening, reaching its low of 6.5575 nearly a year later. Although the Rand traded in a channel, 6.7275 supports to 7.0280 resistances, it lost its footing in August of 2010 weakening to 8.5927 to the dollar by November of 2010; a 27.73% decline vs the US Dollar. The Rand rallied a bit in 2011 reaching a low against the US Dollar at 7.4397 Rand in March 2011. From that point, the South African Rand began a steady, long term weakening trend with a few short lived rallies along the way vs the US Dollar. Granted, the dollar has been ‘on a tear’ vs all the majors; let alone the South Africa Rand for some time now as seen in the chart.

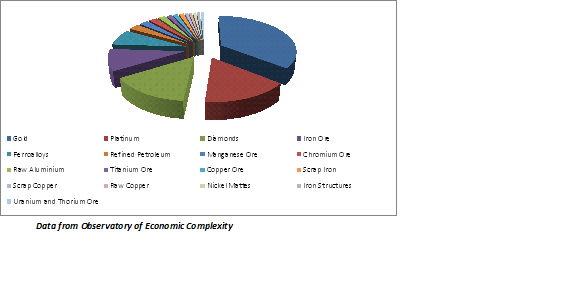

However, there are indeed domestic as well as exogenous reasons for astonishing 98.4% decline from the April 2010 low of 6.5575. Of South Africa’s top 50 exports, 17 are either gold, diamonds or metal ores including Uranium, accounting for nearly half of all South Africa’s exports. Conversely, over just over 20% of South Africa’s imports are crude or refined petroleum products.

Lastly, China and India, currently experiencing economic contractions account for 27% of South Africa’s exports; Japan, Hong Kong, Zimbabwe and the interior areas of Swaziland and Lesotho, all accounting for 34% of exports are also experiencing economic contraction. Lastly, the United States, United Kingdom and Germany accounting for 34% of exports are experiencing slow but stable growth. So the greater part of trading partners are most likely demanding less metal ores, South Africa’s primary exports.

One of the major problems in the South African economy is its poorly maintained infrastructure, particularly in power distribution[i]. Rolling blackouts have become more of the norm than the exception. In January of this year Electric Utility provider Eskom stated that South Africa’s power grid was stressed to the point of “virtually zero” reserve capacity. In spite of having the continent’s second largest economy, South Africa does not have a reliable power grid. Eskom simply did not have the resources to purchase diesel fuel. The issue isn’t just a matter of financing although that does weigh heavily. Political friction and lobbying labor unions have prevented the government from bringing in private sector investors[ii]. The situation somewhat parallels what is happening in Greece as the state owned utility companies are refusing to sell[iii] state owned “assets”. The point being that the continent’s most advanced economy has suffered reduced demand for resources from several major trading partners and must struggle to meet demand from those remaining trading partners whose economies are not contracting.

With the Rand weakening, capital outflows have become a problem for the South African Reserve Bank, forcing higher benchmark rates. In February, official GDP growth forecast were lowered. The official reason was based on the inability of utilities to deliver consistent power to the economy. The 2015 GDP[iv] estimates were lowered to 2% from 2.5%. The full year 2014 GDP measured 1.5%, the lowest in 6 years and a far cry from the 4% pace in 2010 through 2012 which earned its place among the BRICS. At the time the South African Reserve Bank benchmark repurchase rate remained at 5.75%.

In early 2015 US unemployment data was recorded at the high side of estimates increasing the probability that the US Fed would increase rates by mid-year. It was expected that the SARB would increase its own rates to slow capital outflows[v]. However, the decision at the 26 March meeting was in favor of maintaining rates in the interest of supporting the domestic economy. At best, the SARB warned of increasing inflation pressures[vi]. However, the contraction in factory output, down 0.5%, caused prospects of a rate increase to be considered unlikely until at least after mid-year. With declining external demand and the inconsistent power supply, the Rand continued to weaken vs the US Dollar[vii].

As international events escalated tensions between Europe and Russia in the west and China and Pacific nations in the east, the BRICS established an exclusive lending reserve largely funded by Russia and China[viii]. The new reserve facility was intended to provide an alternative to the World Bank and the IMF. Hence, it’s reasonable to assume that the establishment of the exclusive lending facility indicated that neither the World Bank nor the IMF was anxious to provide lending to South Africa (nor to any other BRICS). At the follow SARB meeting, the monetary policy committee decided to again maintain rates at 5.75%[ix]. It should be noted that at this time SARB forecast an annualized 4.6% inflation rate and had repeatedly warned of a rate increase to ‘do whatever it takes’ to maintain financial stability. Also, the Rand continued on its long downward trajectory vs the US Dollar, at 12.1196 by the end of June[x]. Indeed, at the July meeting, Governor Lesetja Kganyago announced a 25 basis point increase in the benchmark repurchase rate[xi]. The monetary policy committee faced a difficult choice: try to slow the accelerating inflation rate or weaken the Rand to keep the mining industry producing in the face of weakening demand. Hence, the bank made the better choice. A devaluation of the Rand would not help commodity exports since advanced economies are still over producing in spite of already stockpiled reserves, such as iron ore and crude petroleum. Further, a rate increase wouldn’t hurt the already contracting economy any more that the malfunctioning power grid, which is slowing the economy far more than benchmark interest rates.

It would be difficult to imagine any actions the South African Reserve Bank could take to strengthen the Rand with its major trading partners seeming to be heading for a recession. Furthermore, aside from the special BRICS lending facility, the SARB does not seem to have the large currency reserves needed to defend the Rand.

Hence, it’s difficult to see the Rand gaining on the US Dollar, particularly, with the Fed warning of impending rate increases.

“CFDs, spread betting and FX can result in losses exceeding your initial deposit. They are not suitable for everyone, so please ensure you understand the risks. Seek independent financial advice if necessary. Nothing in this article should be considered a personal recommendation. It does not account for your personal circumstances or appetite for risk.”

[i] Reuters 7-1-2015

[ii] Forbes 12-1-2015

[iii] Reuters 15-1-2015

[iv] Bloomberg 25-2-2015

[v] Reuters 12-3-2015

[vi] Reuters 26-3-2015

[vii] Bloomberg 9-4-2015

[viii] CNN Money 5-4-2015

[ix] CNBC-Africa 21-5-2015

[x] Bloomberg 22-6-2015

[xi] Financial Times 23-7-2015