The commodity price collapse was well underway in early March when the PBOC reported GDP annualized growth had fallen to 7%, the lowest read in six years . This was on the heels of two PBOC benchmark rate cuts in the last 5 months. At the previous Reserve Bank of Australia monetary policy meeting, 8 April, it was decided to leave the overnight deposit rate unchanged at 2.25%.

The last rate reduction occurred at the February meeting and there was little else the RBA could do. The Australian economy had become heavily dependent on Chinese demand for strategic commodities, particularly metals, in order to supply China’s rapid economic expansion. Now, the PBOC was applying policy tools in order to stop its rapid economic contraction.

Guest post by Mike Scrive of Accendo Markets

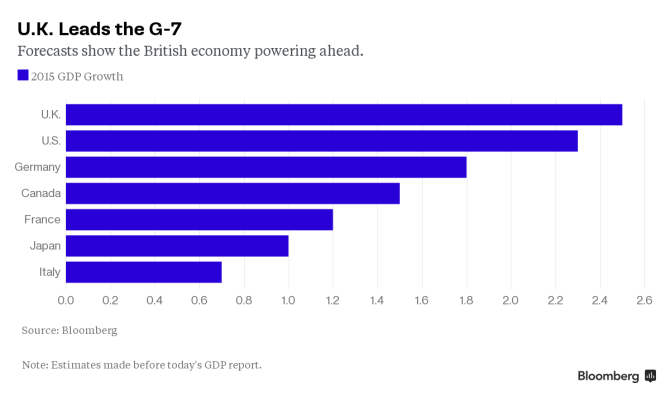

On the other side of the world, the U.K. economy was exhibiting reasonably good performance, but an extreme lack of inflation with the monthly CPI index hardly showing any increase, at times exhibiting deflation. For the next six months, the Bank of England would maintain its Bank Rate at 0.5% as well as its £375 billion asset purchase target. It should be noted that the U.K. biggest trading partners are Europe, in general, and the United States. In March 2015, the ECB initiated its aggressive €60 billion monthly asset purchase program. In other words, the U.K. was experiencing stable economic growth as well as having the potential to benefit from expansion on the continent.

A day before the RBA May meeting, HSBC/Markit reported a sharp decline in Chinese PMI, the most in a year. That reading, in addition to previous weak economic data, may have been the deciding factor to reduce the overnight cash rate another 25 basis points to 2.00%. As the chart demonstrates, it may have also been a deciding factor for currency traders to sell the Aussie and buy Pound Sterling. The Aussie began a long and sustained weakening trend from about that point to the 8 September high of $2.19895 to Pound Sterling; a 16.237% decline from the 25 March GBP/AUD low of 1.89178.

Competition in the commodities market was intensifying as noted by Glencore’s CEO, Mr. Ivan Glasenberg : “…Unfortunately, our competitors, the world, have produced more supply than demand and commodity prices are down for that reason… …I’m doing my level best to convince my competitors we should understand the words demand-supply…” The situation was similar in crude oil markets with excessive supply combined with continuing high production and a sudden decline in demand were driving prices to lows not seen in years.

The PBOC was under pressure to take more action and the incoming data seem to be a turning point : CPI was increasing at 1.5% annualized, PPI fell 4.6%, exports fell 6.4% in the previous month and overall trade fell 11%. On 9 May the PBOC cut its 1-year deposit rate to 2.25%.

On the other side of the world, UK CPI experienced a month over month decline of -0.1%, however economic growth while far from self-sustaining, was not shrinking . Further, bolstered by a strong Pound, lower fuel prices and lower import prices gave a lift to consumer confidence. The point being that the UK economy was far from contracting.

As if the contracting Chinese economy wasn’t enough, China’s equity markets began to correct, with the Shanghai index dropping more than 6% and the Hang Seng over 2%, 28 May . At the RBA 3 June meeting, it was decided that the Bank would remain ‘actively neutral’, indicating its willingness to reduce rates further at an appropriate future time . It should be noted that the RBA was caught between reacting to a regional slowdown or its domestic inflated housing market.

During the month of June, commodity prices, most notably iron ore, copper and crude oil continued to weaken. By the end of June, it seemed that the bottom had dropped out of Chinese stock markets. The PBOC reacted 28 June, reducing benchmark rates : the 1-year deposit 25 basis points to 2.00%, the 1-year borrowing rate to 4.85% and lowered bank reserve ratio requirements.

At the 7 July meeting the RBA held its ground . It should be noted at this point that the Greek-EU impasse was driving a flight to quality trade in Europe, further strengthening the GBP. There was a bit of a reversal as the U.K. economy exhibited strong Q2 GDP growth, for a 10th consecutive month of expansion, thus increasing the probability of a benchmark rate increase. The expansion was drive by the U.K.’s leading business services sector .

The point of the narrative is this. The UK economy is improving; however there are still obstacles, like very low annualized CPI. At its most recent policy meeting the BOE maintained its benchmark Bank Rate at 0.5% as well as its asset purchase target of £375 billion, a sure indication that the BOE is not entirely comfortable with the European or the global situation. The Aussie economy will have some way to go before its all-important commodities sector recovers; very much dependent on China’s future growth rate. If the contraction continues, the RBA has room to reduce rates further to keep its domestic economy from contracting further. However, there’s little they can do to stimulate commodity export demand.

“CFDs, spread betting and FX can result in losses exceeding your initial deposit. They are not suitable for everyone, so please ensure you understand the risks. Seek independent financial advice if necessary. Nothing in this article should be considered a personal recommendation. It does not account for your personal circumstances or appetite for risk.”