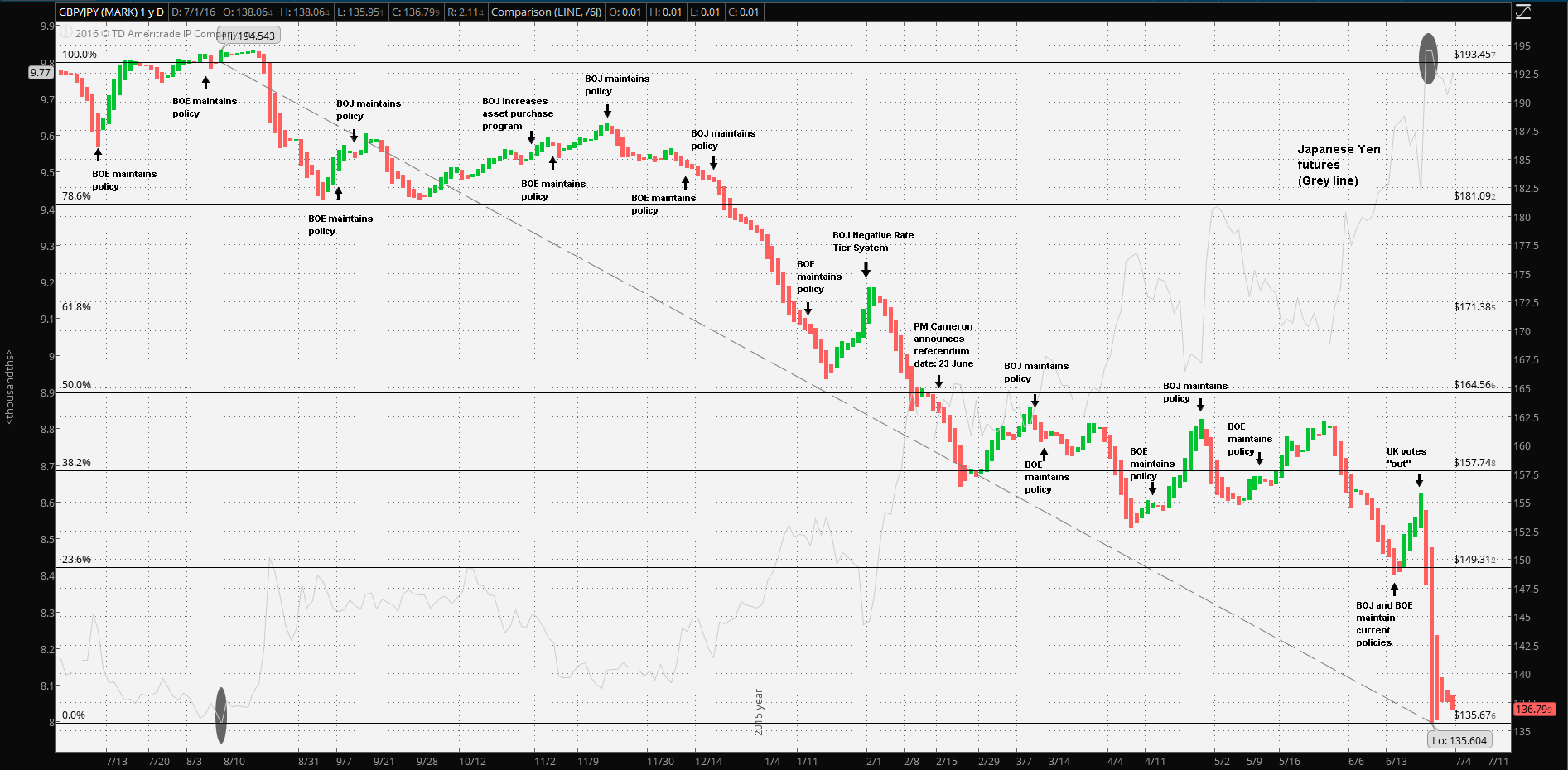

The most recent Bank of Japan monetary policy meeting adjourned 15 June, just one week before the UK referendum vote. The question must be asked whether the BOJ considered any risk to the Japanese economy either before or after the vote. True, there is an important relation between the Sterling and the Yen as IMF world reserve currencies. As the chart below demonstrates the Yen gained sharply on Sterling immediately following the referendum’s official tally. On the day of the referendum, the market priced ¥155.81 per GBP. By 27 June, the Yen gained nearly 13% on Sterling reaching a 52 week low of ¥135.604. To be fair, the Yen had also gained against other majors likely in a flight-to-quality trade and no doubt, much to the frustration of the BOJ.

It’s worth noting, however, that although this was a sharp and likely reactionary move, the Yen has gained steadily and significantly on Sterling over the past 52 weeks. The 52 week Sterling best exchanged one GBP at ¥194.543, 11 August, 2015. Referring again to the chart below, the Yen trended higher before leveling off around 24 February 2016 and then remained in a range of ¥152.76 resistance to ¥163.40 support. Beginning 1 June, Yen broke the short term resistance to ¥148.68, retraced a bit and then spiked to the ¥135.604 high, 27 June 2016. From 52 week low to 52 week high, the Yen gained a remarkable 30.296%. At this point it’s important to note that for most of the past 52 weeks the UK referendum was merely speculation. It wasn’t until 19 February that PM Cameron announced an official date for a referendum vote. Oddly, that coincided with the beginning of the short term GBP/JPY trading range which lasted until June. So, was the secession vote a major issue for the Yen or perhaps an excuse to simple pile into Yen as part of a long, ongoing trend?

Guest post by Mike Scrive of Accendo Markets

The UK accounts for a mere 1.5% of the Japanese export market and only 0.87% of Japanese imports originate from the UK; hence it’s reasonable to conclude that this isn’t a trade parity issue.

One likely reason is the relational position of Pound Sterling to other IMF Special Drawing Rights currencies. It’s important to consider a few points. According to the IMF “...The SDR is neither a currency, nor a claim on the IMF. Rather, it is a potential claim on the freely usable currencies of IMF members. Holders of SDRs can obtain these currencies in exchange for their SDRs in two ways: first, through the arrangement of voluntary exchanges between members; and second, by the IMF designating members with strong external positions to purchase SDRs from members with weak external positions…The respective weights of the U.S. dollar, euro, Chinese renminbi, Japanese yen, and pound sterling are 41.73 percent, 30.93 percent, 10.92 percent, 8.33 percent, and 8.09 percent …”

It’s not unreasonable to conclude that financial institutions, including advanced economy central banks as well as emerging market central banks are reallocating reserves in the wake of Brexit. Keep in mind that many emerging market economies have issued debt in foreign currencies and that debt was likely purchased by institutions under low or negative rate policy regimes. Also, the Renminbi has weakened over the past year and now both Sterling and Euro have uncertain near term futures. Not to mention the rising potential for BOE and ECB key rate reductions. Thus, the most secure remaining SDR ‘safe havens’ are US Dollar and Japanese Yen. (Although not a part of the SDR basket, safe haven reallocation may also been seen in the Swiss Franc. So much so, in fact, SNB policy is specifically targeting relentless capital inflow).

An even more dramatic indication of the ‘depth’ of a global flight to quality trade, in spite of the cost, was reported by Fitch 29 June: “…Investors’ flight to safe assets following the UK’s EU referendum on June 23 pushed the global total of sovereign debt with negative yields to $11.7 trillion as of June 27, up $1.3 trillion from the end-May total, according to new analysis by Fitch Ratings. Brexit-related concerns drove more long-dated bond yields negative, with particularly big shifts in German, French and Japanese yield curves during June…”

In its most recent policy meeting statement, the BOJ reiterated its domestic concerns and its main global concerns are still focused on China, the US and “…the European debt problem and the momentum of economic activity and prices in Europe, and geopolitical risks…” So the BOJ merely makes mention of obvious global concerns but is clearly not specifically concerned over the referendum vote.

The point of the matter is that with the Brexit vote resolved, there are now two fewer safe-haven currencies, Pound Sterling and Euro, at least for the foreseeable future. The BOJ will eventually have to take action, particularly with the Yen approaching parity with the US Dollar. The question is not so much as the BOJ weakening the Yen against all the majors, but rather how will Sterling react relative to a BOJ action. All things considered, it’s not unreasonable to expect Sterling to not respond significantly to BOJ action, or perhaps weaken further until a Brexit unwind plan is in place.