GBP/USD never fully recovered from the devastating flash crash but the team at Goldman Sachs sees further room to the downside:

Here is their view, courtesy of eFXnews:

Since we reiterated our 3-month target of 1.20 for GBP/$, Cable has fallen sharply to within striking distance of our forecast*.

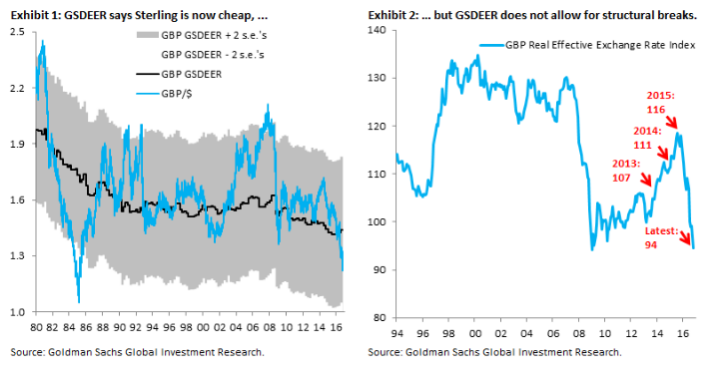

Given how much Sterling has now fallen, much of the market dialogue revolves around the idea of “fair value”,with many making the point that the Pound is now very cheap. Indeed, on our fair value model for exchange rates, something we call GSDEER, GBP/$ is now slightly more than one standard deviation cheap, the first material undervaluation in a long time (Exhibit 1). The problem is that GSDEER and models like it tend to generate estimates for fair value that are essentially long-term moving averages of the exchange rate, which means that they do not allow for structural breaks of the kind that the referendum and the rising odds of a “hard” Brexit clearly represent. In other words, fair value in models such as GSDEER has likely jumped lower, although the extent to which this is the case is difficult (and somewhat arbitrary) to model.

For lots more FX trades from major banks, sign up to eFXplus

By signing up to eFXplus via the link above, you are directly supporting Forex Crunch.

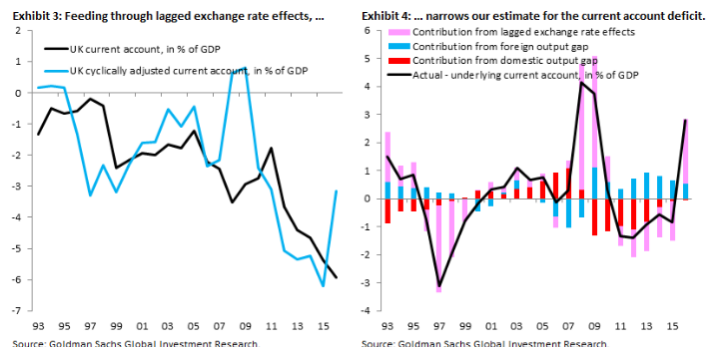

We therefore pursue a different approach, estimating the kind of exchange rate adjustment needed for the UK current account deficit to shrink to some target level. This kind of model, also called the macro-balance approach, is used by the IMF in its exchange rate valuation assessment across countries. The model generates an estimate for the underlying current account, closing the domestic and foreign output gaps and feeding through lagged effects of exchange rate changes.

Exhibit 3 shows our estimates for the underlying (cyclically adjusted) current account (blue line), together with the actual current account (black line). Exhibit 4 maps the difference in these two lines into the contributions from closing the domestic and foreign output gaps and feeding through lagged exchange rate changes.

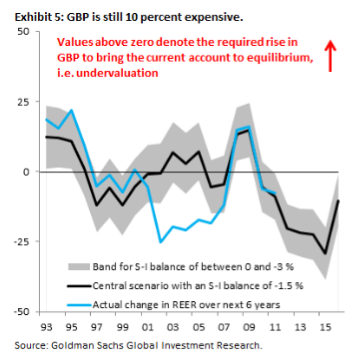

The black line in Exhibit 5 shows the evolving exchange rate assessment for the British Pound using this approach. It shows the move in the real effective exchange rate that is required to bring the underlying current account to -1.5 percent. Given the sharp devaluation that has already occurred, this number is now -10.3 percent, i.e., Sterling would have to fall another 10 percent for the underlying current account to go from its current level (-3.0 percent) to -1.5 percent. The grey area around the black line gives the upper and lower bounds for the exchange rate adjustment if we assume that the underlying current account needs to move to -3.0 percent and 0.0 percent, respectively. In the former case, given that the underlying current account is already at -3.0, the required GBP move weaker is essentially zero, while it is closer to 20 percent if the current account needs to close entirely. These estimates are obviously subject to large uncertainties.

As we note above, the trade elasticities we use may be too optimistic, which would mean that the required Sterling fall is bigger than we show here. It is also quite possible that the current account doesn’t need to shrink as much, if the UK is eventually able to negotiate a “soft” Brexit. That said, our main result is that – even with the large declines that have already occurred – the trade-weighted Pound is still around 10 percent overvalued if a smaller current account deficit is the norm going forward. In short, Sterling is not yet cheap.

For lots more FX trades from major banks, sign up to eFXplus

By signing up to eFXplus via the link above, you are directly supporting Forex Crunch.